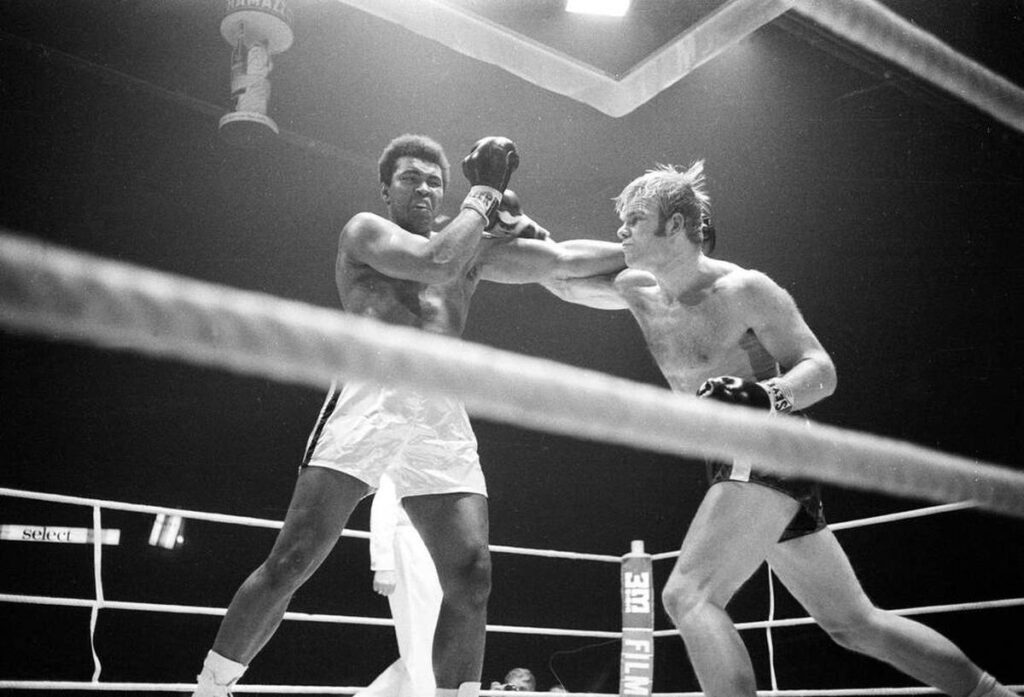

On Boxing Day 1971, the sporting world turned its attention to German boxer Jürgen Blin, whose unorthodox style had Muhammad Ali on the ropes.

His father was an alcoholic milkman, and his childhood was marked by teasing about his rural origins.

As a teenager, he scraped by as a ship’s boy before a successful apprenticeship as a butcher seemed to be the best life had to offer him.

But then Jürgen Blin from Burg on Fehmarn discovered that he had a talent that would take him even further—to the New York Times, for example.

“The big mismatch was not as one-sided as expected,” wrote about him more than 50 years ago: “Jürgen Blin proved to be an exciting opponent for the former world champion.”

Muhammad Ali was the former world champion in question: on Boxing Day 1971, Blin fought the fight of his life against him. It was a fight that created a regional legend from which Blin benefited until the end of his professional career.

Muhammad Ali praised Blin’s determination

For Ali, his third fight against a German opponent – after Willi Besmanoff in 1961 and Karl Mildenberger in 1966 – was a warm-up fight, part of his long journey between the lost “Fight of the Century” against Joe Frazier in March 1971 and his second world championship victory in the “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman in 1974.

For Blin, the Christmas fight at Zurich’s Hallenstadion came about because two other potential Ali opponents had dropped out. He was not considered an opponent on equal footing, having already lost nine of his 42 professional fights.

But Blin was determined to give it his all – and went further than anyone expected: For several rounds, he surprised Ali with unorthodox tactics, fearlessly throwing himself into his left lead hand and trying to throw the ring legend off balance with counterpunches. It took Ali a long time to get the upper hand over his supposed easy opponent – and finally knock him out in the seventh round.

Afterwards, he praised his limited but energetic opponent: “He didn’t have the skill, but he had the will, and sometimes the will can defeat the skill.”

Jürgen Blin successfully ran a snack bar and pub

It wasn’t enough for Blin to defeat “the skill,” but it was enough for a performance that earned him respect and financial benefits for the rest of his life.

Blin, father of Knut Blin, who died prematurely in 2004, later earned his living as a snack bar and pub owner, and his own story was the biggest attraction in his establishments. “I earned around a million from boxing, but I didn’t do too badly with the pubs either,” he once told Die Welt.

The fame was a kind of poetic justice for a career obstacle through no fault of his own: Blin was never really a true heavyweight and would be classified as a cruiserweight today – but that weight class did not exist in his day.